- Home

- Barry Eisler

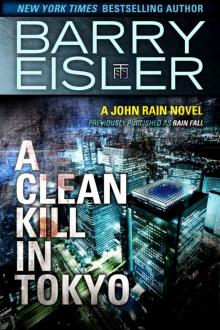

A Clean Kill in Tokyo (previously published as Rain Fall)

A Clean Kill in Tokyo (previously published as Rain Fall) Read online

A CLEAN KILL IN TOKYO

Previously published as Rain Fall

Name: John Rain.

Vocation: Assassin.

Specialty: Natural Causes.

Base of operations: Tokyo.

Availability: Worldwide.

Half American, half Japanese, expert in both worlds but at home in neither, John Rain is the best killer money can buy. You tell him who. You tell him where. He doesn’t care about why…

Until he gets involved with Midori Kawamura, a beautiful jazz pianist—and the daughter of his latest kill.

“Eisler provides a cracklingly good yarn, well written, deftly plotted, and surprisingly appealing… Thomas Perry and Lawrence Block need not retire their hit men quite yet, but Eisler is clearly a challenger.”

—Boston Globe

Includes a note from the author introducing the new edition.

CONTENTS

EBOOK SETTINGS • DEDICATION • INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION • REMOTELY HACKING A PACEMAKER • A NOTE ON THE NEW TITLES

EPIGRAPH

PART I

CHAPTER 1 • CHAPTER 2 • CHAPTER 3 • CHAPTER 4 • CHAPTER 5 • CHAPTER 6 • CHAPTER 7 • CHAPTER 8 • CHAPTER 9 • CHAPTER 10 • CHAPTER 11 • CHAPTER 12 • CHAPTER 13

PART II

CHAPTER 14 • CHAPTER 15 • CHAPTER 16 • CHAPTER 17 • CHAPTER 18

PART III

CHAPTER 19 • CHAPTER 20 • CHAPTER 21 • CHAPTER 22 • CHAPTER 23 • CHAPTER 24 • CHAPTER 25 • CHAPTER 26

AUTHOR’S NOTE • ACKNOWLEDGMENTS • ABOUT THE AUTHOR • ALSO BY BARRY EISLER • CONTACT BARRY

COPYRIGHT

EBOOK SETTINGS

This ebook uses custom fonts. The publisher recommends the following settings for your Kindle device or app:

Kindle Fire, Kindle Fire HD

These devices automatically display the ebook as the author and publisher have intended. No special settings are required.

Kindle Paperwhite, Kindle 4 Touch

Tap the top of the screen to open the device’s Toolbar. When the Fonts window appears, tap the Aa button and select the Publisher Font option. In the upper right corner of the Fonts window, tap the X to close the window to return to the ebook.

Kindle 5, Kindle 4

On the front of the device, press the Menu button. When the dialog window appears, use the 5-way button to select Change Font Size. Select the Publisher Font option. Press the Menu button to close the dialog window to return to the ebook.

Kindle Keyboard

On the front of the device, press the Aa button. When the dialog window appears, use the 5-way button to select on to the right of the Publisher Font option. The dialog window closes automatically.

Kindle for PC, Kindle for Mac, Kindle for Android

These apps automatically display the ebook as the author and publisher have intended. No special settings are required.

Kindle DX, Kindle for iPad, Kindle Cloud Reader

As of the publication of this ebook, these do not support custom fonts. No special settings are required.

This novel is for three people who are not here to read it.

For my father, Edgar, who gave me strength.

For my mother, Barbara, who gave me insight.

For my brother, Ian, who helped me climb the mountain, whose memory keeps me climbing still.

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

A Clean Kill in Tokyo was my first try at a novel. I started writing it when I was living in Tokyo in 1993, when my protagonist, assassin John Rain, would have been forty-one or so. I didn’t know then the book wouldn’t be published until 2002, or that it would be the start of a series that includes seven entries (so far). If I had known, I might have given Rain a different backstory and made him younger. But I’m not sorry I didn’t. I like the way aging has changed and challenged him. He’s not as physically quick as he once was, but he’s smarter, and as the saying goes, old age and treachery will beat youth and reflexes every time.

Having reread the book for the new release, I have to say I’m pleased with how well it’s held up. I tightened up the language here and there, and there are a few technological anachronisms (who uses pagers anymore?), but other than that, the story still strikes me as solid. The premise of its opening sequence—that you can remotely short out a pacemaker—has subsequently been vindicated (see the link below). And its themes—governmental corruption; the way power accrues to whatever factions hold the most information about others; the tension between the need to make things better and the urge to protect the self—are as relevant as ever, perhaps more so.

It’s interesting for me to look back at the story and consider where it came from. I think it all started with my long-standing interest in what I like to think of as “forbidden knowledge”: methods of unarmed killing; surveillance and counter-surveillance; lock picking; breaking and entry; and other arcana the government wants only a few select individuals to know. When I was a kid, I read a biography of Harry Houdini, and in the book a cop was quoted as saying, “It’s fortunate Houdini never turned to a life of crime, because, if he had, he would have been difficult to catch and impossible to hold.” I remember thinking how cool it was that this man knew things ordinary people weren’t supposed to know, things that gave him special power, and I guess that fascination never left me. Over the years, I’ve amassed an unusual library from Paladin Press and the now tragically defunct Loompanics Unlimited (“The Lunatic Fringe of the Libertarian Left”) on some fairly esoteric subjects, with titles such as The Death Investigator’s Handbook, 21 Techniques of Silent Killing, How to Escape From Controlled Custody, How to Disappear and Never Be Found, and many others. I also got into a variety of martial arts, and spent three years in the CIA, where I learned some of that forbidden knowledge firsthand, courtesy of Uncle Sam.

And then I moved to Tokyo, and living in that incredible city—training in judo at the Kodokan; frequenting the jazz clubs and coffee houses and whisky bars; feeling what it’s like to be within a culture but still an outsider—somehow catalyzed and combined with my existing forbidden knowledge proclivities. One morning, while commuting to work, a vivid image came to me of two men following another man down Dogenzaka Street in Shibuya. I still don’t know where the image came from, but I started thinking about it. Who are these men? Why are they following that other guy? Then answers started to come: They’re assassins. They’re going to kill him. But these answers led to more questions: Why are they going to kill him? What did he do? Who do they work for? It felt like a story, somehow, so I started writing, and before long, I was working on a novel about a half-Japanese, half-American hitman whose specialty was making it look like natural causes. I envisioned a judo expert and combat veteran, with a taste for good coffee and rare single malt whisky and a quiet passion for live jazz; a man who resides in Tokyo and is of the city while not belonging to it; a perpetual outsider who secretly wants in; a man who tried and failed to be samurai and is now only ronin.

That man became John Rain, and the book, A Clean Kill in Tokyo. In retrospect, I’m amazed I didn’t immediately realize that the book was more than a standalone, that a character as complex and conflicted as Rain would be a great protagonist for a series. But better late than never. I enjoyed reacquainting myself with Rain in connection with this rerelease of the series. I hope you’ll enjoy your time with him at least as much.

Remotely hacking a pacemaker:

http://blogs.computerworld.com/cybercrime-and-hacking/21163/pacemaker-hacker-says-worm-could-possibly-commit-mass-murder

A NOTE ON THE NEW TITLES

> Why have I changed the titles of the Rain books? Simply because I’ve never thought the titles were right for the stories. The right title matters—if only because the wrong one has the same effect as an inappropriate frame around an otherwise beautiful painting. Not only does the painting not look good in the wrong frame; it will sell for less, as well. And if you’re the artist behind the painting, having to see it in the wrong frame, and having to live with the suboptimal commercial results, is aggravating.

The sad story of the original Rain titles began with the moniker Rain Fall for the first in the series. It was a silly play on the protagonist’s name, and led to an unfortunate and unimaginative sequence of similar such meaningless, interchangeable titles: Hard Rain, Rain Storm, Killing Rain (the British titles were better, but still not right: Blood from Blood for #2; Choke Point for #3; One Last Kill for #4). By the fifth book, I was desperate for something different, and persuaded my publisher to go with The Last Assassin, instead. In general, I think The Last Assassin is a good title, but in fairness it really has nothing to do with the story in the fifth book beyond the fact that there’s an assassin in it. But it was better than more of Rain This and Rain That. The good news is, the fifth book did very well indeed; the bad news is, the book’s success persuaded my publisher that assassin was a magic word and that what we needed now was to use the word assassin in every title. And so my publisher told me that although they didn’t care for my proposed title for the sixth book—The Killer Ascendant—they were pleased to have come up with something far better. The sixth book, they told me proudly, would be known as The Quiet Assassin.

I tried to explain that while not quite as redundant as, say, The Deadly Assassin or The Lethal Assassin, a title suggesting an assassin might be notable for his quietness was at best uninteresting (as opposed to, say, Margret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin, which immediately engages the mind because of the connection of two seemingly contradictory qualities). The publisher was adamant. I told them that if they really were hell-bent on using assassin in a title that otherwise had nothing to do with the book, couldn’t we at least call the book The Da Vinci Assassin, or The Sudoku Assassin? In the end, we compromised on Requiem for an Assassin, a title I think would be good for some other book but is unrelated to the one I wrote—beyond, again, the bare fact of the presence of an assassin in the story.

Now that I have my rights back and no longer have to make ridiculous compromises about these matters, I’ve given the books the titles I always wanted them to have—titles that actually have something to do with the stories, that capture some essential aspect of the stories, and that act as both vessel and amplifier for what’s most meaningful in the stories. For me, it’s like seeing these books for the first time in the frames they always deserved. It’s exciting, satisfying, and even liberating. Have a look yourself and I hope you’ll enjoy them.

In the changing of the times, they were like autumn lightning, a thing out of season, an empty promise of rain that would fall unheeded on fields already bare.

—Shosaburo Abe,

master swordsman, on the Meiji era samurai

PART I

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

—But who is that on the other side of you?

—T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land

CHAPTER 1

Harry moved through the morning rush-hour crowd like a shark fin cutting through water. I was following twenty meters back on the opposite side of the street, sweating with everyone else in the unseasonable October Tokyo heat, and I couldn’t help admiring how well the kid had learned what I’d taught him. He was like liquid the way he slipped through a space just before it closed, or drifted to the left to avoid an emerging bottleneck. The changes in Harry’s cadence were accomplished so smoothly that no one would recognize he had altered his pace to narrow the gap on our target, who was now moving almost conspicuously quickly down Dogenzaka toward Shibuya Station.

The target’s name was Yasuhiro Kawamura. He was a career bureaucrat connected with the Liberal Democratic Party, or LDP, the political coalition that has been running Japan almost without a break since the war. His current position was Vice Minister of Land and Infrastructure at the Kokudokotsusho, the successor to the old Construction Ministry and Transport Ministry, where obviously he had done something to seriously offend someone because serious offense is the only reason I ever get a call from a client.

I heard Harry’s voice in my ear: “He’s going into the Higashimura fruit store. I’ll set up ahead.” We were each sporting a Danish-made, microprocessor-controlled receiver small enough to nestle in the ear canal, where you’d need a flashlight to find it. A voice transmitter about the same size goes under the jacket lapel. The transmissions are burst, which makes them hard to pick up if you don’t know exactly what you’re looking for, and they’re scrambled in case you do. The equipment freed us from having to maintain constant visual contact, and allowed us to keep moving for a while if the target stopped or changed direction. So even though I was too far back to see it, I knew where Kawamura had exited, and I could continue walking for some time before needing to stop to keep my position behind him. Solo surveillance is difficult, and I was glad I had Harry with me.

About twenty meters from the Higashimura, I turned into a drugstore, one of the dozens of open-façade structures that line Dogenzaka, catering to the Japanese obsession with health nostrums and germ fighting. Shibuya is home to many different buzoku, or tribes, and members of several were represented here this morning, united by a common need for one of the popular bottled energy tonics in which the drugstores specialize—tonics claiming to be bolstered with ginseng and other exotic ingredients but delivering instead with a more prosaic jolt of ordinary caffeine. Waiting in front of the register were a few gray-suited sarariiman—”salary man” corporate rank and file—their faces set, cheap briefcases dangling from tired hands, fortifying themselves for another interchangeable day in the maw of the corporate machine. Behind them, two empty-faced teenage girls, their hair reduced to steel wool brittleness by the dyes they used to turn it orange, noses pierced with oversized rings, their costumes meant to proclaim rejection of the traditional route chosen by the sarariiman in front of them but offering no understanding of what they had chosen instead; a gray-haired retiree, his skin sagging but his face oddly bright, probably in Shibuya to avail himself of one of the area’s well-known sexual services, which he would pay for out of a pension account he kept hidden from his wife, not realizing she knew what he was up to and simply didn’t care.

I wanted to give Kawamura about three minutes to get his fruit before I came out, so I examined a selection of bandages affording a view of the street. The way he had ducked into the store looked like a move calculated to flush surveillance, and I didn’t like it. If we hadn’t been hooked up the way we were, Harry would have had to stop abruptly to maintain his position behind the target. He might have had to do something ridiculous—drop to tie his shoe, stop to read a street sign—and Kawamura, probably peering out from the store’s entrance, could have made him. Instead, I knew Harry would continue past the fruit store; he would stop about twenty meters ahead, give me his location, and fall in behind when I told him the parade was moving again.

The fruit store was a good spot to turn off, all right—too good for someone who knew the route to have chosen it by accident. But Harry and I weren’t going to be flushed out by beginner moves from some government antiterrorist primer. I’ve had that training. It’s the beginning of skill, not the end of it.

I left the drugstore and continued down Dogenzaka, more slowly than before because I had to give Kawamura time to exit the store. Shorthand thoughts shot through my mind: Are ther

e enough people between us to obscure his vision if he turns when he comes out? What shops am I passing if I need to duck off suddenly? Is anyone looking up the street at the people heading toward the station, maybe helping Kawamura spot surveillance? If I had already drawn any countersurveillance attention they might notice me now, because before I was hurrying to keep up with the target and now I was taking my time, and people on their way to work don’t change their pace that way. But Harry had been the one walking point, the more conspicuous position, and I hadn’t done anything to arouse attention before stopping in the drugstore.

I heard Harry again: “I’m at 109.” Meaning he had turned into the landmark 109 Department Store, famous for its collection of one hundred and nine restaurants and trendy boutiques.

“No good,” I told him. “The first floor is lingerie. You going to blend with fifty teenage girls in blue sailor school uniforms picking out padded bras?”

“I was planning to wait outside,” he replied, and I could imagine him blushing.

The front of 109 is a popular meeting place, typically crowded with a variegated collection of pedestrians. “Sorry, I thought you were going for the lingerie,” I said, suppressing the urge to smile. “Just hang back and wait for my signal as we go past.”

“Right.”

The fruit store was only ten meters ahead, and still no sign of Kawamura. I was going to have to slow down. I was on the opposite side of the street, outside Kawamura’s probable range of concern, so I could risk stopping, maybe to fiddle with a mobile phone. Still, if he looked, he would spot me standing there, even though, with my father’s Japanese features, I don’t have a problem blending into the crowds. Harry—a pet name for Haruyoshi—being born of two Japanese parents, has never had to worry about sticking out.

All the Devils

All the Devils Requiem for an Assassin

Requiem for an Assassin The Killer Collective

The Killer Collective The Chaos Kind

The Chaos Kind The God's Eye View

The God's Eye View Paris is a Bitch

Paris is a Bitch The Khmer Kill: A Dox Short Story (Kindle Single)

The Khmer Kill: A Dox Short Story (Kindle Single) The Last Assassin

The Last Assassin The Detachment

The Detachment The Night Trade (A Livia Lone Novel Book 2)

The Night Trade (A Livia Lone Novel Book 2) Fault Line

Fault Line Hard Rain

Hard Rain The Khmer Kill_A Dox Short Story

The Khmer Kill_A Dox Short Story London Twist: A Delilah Novella

London Twist: A Delilah Novella The Lost Coast

The Lost Coast Rain Fall

Rain Fall Zero Sum

Zero Sum Killing Rain

Killing Rain John Rain 08: Graveyard of Memories

John Rain 08: Graveyard of Memories A Clean Kill in Tokyo (previously published as Rain Fall)

A Clean Kill in Tokyo (previously published as Rain Fall) Inside Out: A novel

Inside Out: A novel John Rain 07 - The Detachment

John Rain 07 - The Detachment Graveyard of Memories

Graveyard of Memories The Lost Coast -- A Larison Short Story

The Lost Coast -- A Larison Short Story Zero Sum (A John Rain Novel)

Zero Sum (A John Rain Novel)